The Quarterly Assessment: An April 2017 Special Edition |

The Broken Window Theory and Your Community Associationby Daniel B. Streich

Walt Disney intuitively figured it out and adopted it even before the sociologists came up with it. Rudy Giuliani wholeheartedly believed in it and implemented it during his tenure as Mayor of New York City. What is “it”? An analysis of human behavior known as the “broken window theory.” We think it applicable to community associations as well. A few qualifiers at the outset. When the concept was first published in 1982 in the Atlantic Monthly by noted social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling, it was initially perceived as a theory pertaining to urban criminology. That is essentially how it was applied and implemented by Giuliani during his tenure as the chief executive of New York City, where it achieved dramatically successful results, both statistically and empirically. But the theory has since been discussed and applied in other academic disciplines and spheres of human activity as well, with economics as one example.

We acknowledge here that the broken window theory has its critics. Nevertheless, there is a compelling, real-life quality to the theory. It seems to have an undeniable explanatory and predictive capacity. Many – perhaps most – Americans are able to recall experiences or places in their lives in which the theory seems to have been validated, in whole or in part.

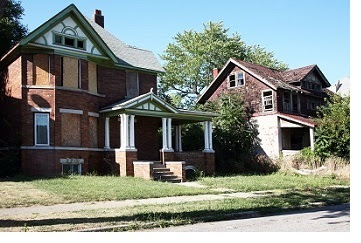

So what is the theory? Reduced to its simplest form, it uses a broken window as a symbolic metaphor. The theory holds that if an abandoned building or a vacated residential dwelling has a broken window that is visible to the public, and if that window goes unrepaired, more windows in the building or the dwelling will soon be broken by acts of vandalism. If the owner or the community allows the deterioration of the building to continue to go unrepaired and unchecked, then eventually squatters may wind up living in the building, or minors may play in the building and commit further acts of vandalism, or drug users may use the building as a “shooting gallery” to indulge their addiction. Wilson, Kelling and other sociologists performed some practical experiments to test and prove the theory, but a description of those experiments, while fascinating, is beyond the scope of this article. So what is the theory? Reduced to its simplest form, it uses a broken window as a symbolic metaphor. The theory holds that if an abandoned building or a vacated residential dwelling has a broken window that is visible to the public, and if that window goes unrepaired, more windows in the building or the dwelling will soon be broken by acts of vandalism. If the owner or the community allows the deterioration of the building to continue to go unrepaired and unchecked, then eventually squatters may wind up living in the building, or minors may play in the building and commit further acts of vandalism, or drug users may use the building as a “shooting gallery” to indulge their addiction. Wilson, Kelling and other sociologists performed some practical experiments to test and prove the theory, but a description of those experiments, while fascinating, is beyond the scope of this article.Why does this happen? Fundamentally, the theory’s insight is that people are both adaptive and imitative beings. A person is adaptive in that he or she will usually conform their behavior to what they perceive to be the “norm” in their environment, so as to adapt and survive in that environment. In so doing they are essentially imitating those around them. A broken window that goes unrepaired sends a signal to the community. It implicitly communicates a message to the people who observe that minor but continuing indicator of social disorder. That message? No one cares. And if no one cares enough to repair one window, then the community won’t care if more windows are broken, or if further acts of vandalism or social disorder are committed. In fact and effect, an unrepaired broken window – or litter on the street, or graffiti on fences – visually degrades the social order of that community and precipitates an ongoing decline of the acceptable and desirable social norm.

Decades before Wilson and Kelling developed and published their broken window theory, Walt Disney – being the genius that he was – intuitively understood this aspect of human nature. When he opened his first theme park (Disneyland in Anaheim, California) during the 1950s, he continually emphasized to his staff (paraphrasing here): We will maintain our park in an immaculate condition, always… when our guests walk into our park in the morning, they will encounter a pristine environment, as perfectly maintained as humanly possible… we will strive ceaselessly to maintain the park in that condition throughout the day… when corrective maintenance is required, we will do it at night, so that when our guests stream through our gates every morning, they will find themselves in a wonderfully well-ordered and clean environment. Decades before Wilson and Kelling developed and published their broken window theory, Walt Disney – being the genius that he was – intuitively understood this aspect of human nature. When he opened his first theme park (Disneyland in Anaheim, California) during the 1950s, he continually emphasized to his staff (paraphrasing here): We will maintain our park in an immaculate condition, always… when our guests walk into our park in the morning, they will encounter a pristine environment, as perfectly maintained as humanly possible… we will strive ceaselessly to maintain the park in that condition throughout the day… when corrective maintenance is required, we will do it at night, so that when our guests stream through our gates every morning, they will find themselves in a wonderfully well-ordered and clean environment.One of my memories – still – from family vacations to Disneyland in my early childhood is of high school and college-aged young people, attired in straw boaters and spotlessly clean, light pastel-colored Disneyland staff uniforms, equipped with short-handled mini-brooms and dustbins attached to three-foot poles, constantly walking around the park, scooping up every straw wrapper, cigarette butt, candy wrapper and every other possible item of refuse and debris that didn’t belong in Disneyland. That was their job. Their conscientious diligence and the scope of their activity impressed me, even at five years of age.

Why the unceasing effort? Because as Walt Disney informed his staff, people who come into an unsullied and orderly environment will be more likely to keep it that way. They will adapt to the norm set by that environment and they will therefore be more likely to respect Disneyland and their fellow guests. It didn’t work on every guest’s subconscious, of course, but it had – and has – the desired general effect, and Disney Corporation’s philosophy in that regard continues to the present day.

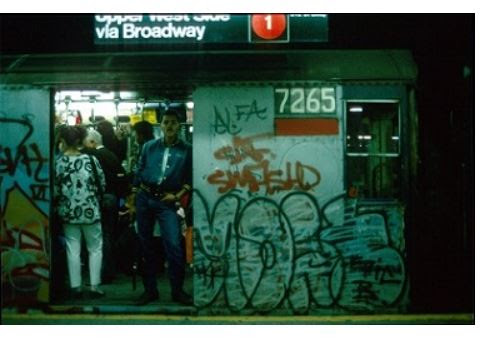

Similarly, and in the urban criminology scenario, former NYC Mayor Giuliani implemented the theory to pull New York City back from the precipice of anarchy. Not many sentient individuals who were familiar with that city during the ’70s and ’80s would disagree with a description of the Big Apple as a chaotic, threatening, crime-ridden, nearly ungovernable entity. Its tourist trade had sunk through the floor. When he became NYC’s Mayor, Giuliani faced a challenge that made the Augean stables seem easy by comparison.

One might think that Giuliani would have concentrated his efforts on murder, rape, robbery and mayhem. He did so to an extent, but he also paid particular attention to aspects of the NYC environment that previous mayors had ignored. “Squeegee men,” subway turnstile jumpers, graffiti “taggers” and aggressive, physically-intimidating panhandlers suddenly attracted considerable – and unwanted – law enforcement attention from the NYPD. Graffiti in public places, suchas on subway cars, was removed and measures were instituted to prevent its recurrence. Dilapidated properties were sold and redeveloped. Central Park and other “common areas” were physically restored and made safe by a vigilant and visible law enforcement presence. Metaphorically speaking, Giuliani and his staff replaced the broken window. One might think that Giuliani would have concentrated his efforts on murder, rape, robbery and mayhem. He did so to an extent, but he also paid particular attention to aspects of the NYC environment that previous mayors had ignored. “Squeegee men,” subway turnstile jumpers, graffiti “taggers” and aggressive, physically-intimidating panhandlers suddenly attracted considerable – and unwanted – law enforcement attention from the NYPD. Graffiti in public places, suchas on subway cars, was removed and measures were instituted to prevent its recurrence. Dilapidated properties were sold and redeveloped. Central Park and other “common areas” were physically restored and made safe by a vigilant and visible law enforcement presence. Metaphorically speaking, Giuliani and his staff replaced the broken window.The result? New York City became an environment that was no longer menacing in its underlying tone of disorder, crime and chaos. Social order was restored. By reducing the incidence of public and visible lawless acts and social disorder, however minor in nature, Giuliani established and enforced a new social norm, and that signaled to both NYC residents and to potential visitors that Gotham had turned a corner. Tourists returned, crime rates plummeted and the city prospered. New York City’s precipitous decline into anarchic chaos had been arrested, and just in time.

We suspect that by now you have discerned the applicability of the broken window theory to community association governance. What is the norm or prevailing standard in your community? Is your neighborhood generally neat, clean, orderly and well-maintained? Or, conversely, do too many front lawns in your community look like the upland meadows through which Julie Andrews joyfully cavorted in the opening scenes of The Sound of Music? Is peeling paint the norm? Detached gutters? Missing or cockeyed shutters? Garbage cans – or even just garbage – at the curb 24/7? Trailers with watercraft parked in front yards? Broken fences, or even the presence of graffiti? What norm or standard does that appearance communicate to others… say, for example, to potential purchasers who may be driving through your neighborhood?

Because that’s the important point, isn’t it? You may not have known it when you purchased your home in your homeowners or condominium association community. You may not currently understand and appreciate the value of the restrictive covenants and related rules and regulations that govern the appearance and your use of your dwelling. But the fundamental purpose of such restrictions is to preserve the value of your real estate investment. Who among us purchased their home in the hope that they’ll have to sell it someday for less than what they paid for it? Go ahead, raise your hands. Anyone? Didn’t think so.

After that, however, we recommend that a board of directors and the management agent concentrate on minor, more routine violating conditions. As we see it, this approach will accomplish four desirable goals for your association. First, it will hopefully prevent a minor violating condition on a lot (or condominium unit) from deteriorating into larger and more numerous violating conditions on the lot. Second, smaller problems are easier and less expensive to correct than larger problems, and thus property owners are more amenable to fixing smaller problems than having to spend significant amounts of money correcting larger violations. Third, preventing smaller problems from degenerating into larger problems can ultimately save the association from having to resort to litigation to enforce its covenants or use restrictions. And finally, paying attention to the details, the “small stuff,” signals to your community that a reasonable but rigorous norm is being established and will be enforced. Your members may grouse a bit about that, but most of them will understand and appreciate that such a standard actually serves their self-interests, economic and otherwise. And, with the signal having been sent, most of your members will adapt to and abide by the social norm established within your community. After that, however, we recommend that a board of directors and the management agent concentrate on minor, more routine violating conditions. As we see it, this approach will accomplish four desirable goals for your association. First, it will hopefully prevent a minor violating condition on a lot (or condominium unit) from deteriorating into larger and more numerous violating conditions on the lot. Second, smaller problems are easier and less expensive to correct than larger problems, and thus property owners are more amenable to fixing smaller problems than having to spend significant amounts of money correcting larger violations. Third, preventing smaller problems from degenerating into larger problems can ultimately save the association from having to resort to litigation to enforce its covenants or use restrictions. And finally, paying attention to the details, the “small stuff,” signals to your community that a reasonable but rigorous norm is being established and will be enforced. Your members may grouse a bit about that, but most of them will understand and appreciate that such a standard actually serves their self-interests, economic and otherwise. And, with the signal having been sent, most of your members will adapt to and abide by the social norm established within your community.In summary, we acknowledge that one could push the broken window theory too far with respect to its applicability to community association governance and covenant enforcement. But it is instructive as to observable human behavior, and thus when implemented it can support the shared goal of preserving property values in your neighborhood. Fix the window. Mow the lawn. Hide the garbage cans. Set and enforce a norm and thereby send the message that someone cares. All of your members will benefit from that approach, even if they don’t realize it in the short term.

|

|

Photo credits (top to bottom):1. Vandalized warehouse, istockphoto.com/eyecrave |

Like them or not, restrictive covenants establish a baseline, a standard, or yes, a social norm. Hanging toilet seats from a tree in the front yard (to cite an admittedly egregious example from a Louisiana HOA) deviates from and undermines that norm. And yes, the norm established by your restrictive covenants communicates a message to all who enter your community. It signalsto others that the residents in your community take pride in their neighborhood and care about their homes. That attitude may be motivated by community spirit, self-pride and self-dignity, or perhaps just by economic self-interest. Regardless, by setting and enforcing a standard of conscientious maintenance and aesthetic appeal, you’re doing what Walt Disney did for Disneyland… you’re making your community an attractive and welcoming environment which people will enjoy visiting and in which they may want to invest financially and emotionally.So how to accomplish that goal? In the New York City example, Giuliani started with the small things, on the reasoning that if minor but visible and frequent violations were corrected, it would have a salutary effect on the larger problems. Again, that goes to the signaling aspect of the theory. Setting a standard – replacing the window – sends a message. Thus, a community association board of directors should of course take action (legal action, if necessary) against the usual one or two properties in the community that present visual blights within the neighborhood. That enforcement action in and of itself will send a message to the community.

Like them or not, restrictive covenants establish a baseline, a standard, or yes, a social norm. Hanging toilet seats from a tree in the front yard (to cite an admittedly egregious example from a Louisiana HOA) deviates from and undermines that norm. And yes, the norm established by your restrictive covenants communicates a message to all who enter your community. It signalsto others that the residents in your community take pride in their neighborhood and care about their homes. That attitude may be motivated by community spirit, self-pride and self-dignity, or perhaps just by economic self-interest. Regardless, by setting and enforcing a standard of conscientious maintenance and aesthetic appeal, you’re doing what Walt Disney did for Disneyland… you’re making your community an attractive and welcoming environment which people will enjoy visiting and in which they may want to invest financially and emotionally.So how to accomplish that goal? In the New York City example, Giuliani started with the small things, on the reasoning that if minor but visible and frequent violations were corrected, it would have a salutary effect on the larger problems. Again, that goes to the signaling aspect of the theory. Setting a standard – replacing the window – sends a message. Thus, a community association board of directors should of course take action (legal action, if necessary) against the usual one or two properties in the community that present visual blights within the neighborhood. That enforcement action in and of itself will send a message to the community.